The Prisoner in the Asylum: Hammer into Anvil

The introduction and master post to this series of posts about The Prisoner can be found here.

This is the one where Smith/Number 6 makes Number 73 kill herself.

Read that again.

Seriously, he made her kill herself. If you watch the sequence and forget the narrative that The Village is bad and Number 6 is the innocent prisoner it looks very diferent. If Smith hadn't been interfering in somebody else's treatment he wouldn't have had to have been restrained by the attendants and they could have been restraining Number 73 to stop her throwing herself out of the window.

Number 6's sabotage of The Village, his own treatment and Number 73's treatment directly caused this. He has even managed to persuade everyone that he is the victim here! It is quite literally the truth when Number 2 tells him he shouldn't have interfered but of course he blames Number 2 for this.

I'm not advocating slapping patients as Number 2 does, obviously. He has been pushed by Smith into doing something he shouldn't have done. This bit is a commonplace in looking after all sorts of people, but especially people with personality disorders because they can live their 'script' out with the staff in the only way they know how, until they learn to do it differently. The staff should be well able to deal with this if they're any good. Number 2 is clearly in a dynamic with Smith where if he was in a good hospital one of his colleagues would be telling him that he was off Number 6's care, but the inadequate supervision of The Village is rather a given for the show.

I have mentioned before that the Village is trying to get Smith to behave and are appallingly bad at it. They are seeking conformity in a psychiatric sense and that is basically a recipe to wind up someone like Smith. I have mentioned their behavioural approaches before and it is literally clear at every step how they have literally no idea of how to engage him, can't deal with the slightest expression of his personality disorder and are basically a bit rubbish. They are using a straightforward behaviour modification approach which was a commonplace of the old hospitals - you weren't going anywhere, so these approaches could be used because they could contain you for years. You had very simple things to do and would get rewarded for them. For example if you made your bed you would get paid a certain amount or would go on an outing, or whatever. I worked in a 'rehab' unit when I was a student nurse and there was a nurse who could get any of the patients to do literally anything. My mentor told me how wonderful this was and how they didn't know how she did it. I gladly let her know that despite the other nurse not smoking herself it was the box of Benson and Hedges in her handbag which got the patients to do things. There was a certain atmosphere after that.

There is an institutional reason for behaving badly which Goffman calls 'messing up' - it is a sort of lesser impact version of the behaviour which I have previously described when you literally have nothing to lose and just don't care what you do:

'Furthermore, the staff and inmates will be clearly aware of what, in mental hospitals, prisons, and barracks is called "messing up." Messing up involves a complex process of engaging in forbidden activity (including sometimes an effort at escape), getting caught, and receiving something like full punishment. There is usually an alteration in privilege status, categorized by a phrase such as "getting busted." [...] Although these infractions are typically ascribed to the offender's cussedness, villainy, or "sickness," they do in fact constitute a vocabulary of institutionalized actions, but a limited one, so that the same messing up may occur for quite different reasons. [Examples include showing resentment against the institution.] Whatever the meaning imputed to them, messings up have some important social functions for the institution. They tend to limit rigidities which would occur were seniority the only means of mobility in the privilege system; further, demotion through messing up brings old-time inmates into contact with new inmates in unprivileged positions, assuring a flow of information concerning the system and the people in it. (1)

Smith is limiting the institution's rigidity by driving Number 2 off his head! But I think some of the reason for Smith's bad behaviour lies within him.

And so of course for the rest of this post I'm going to focus on Smith's personality disorder.

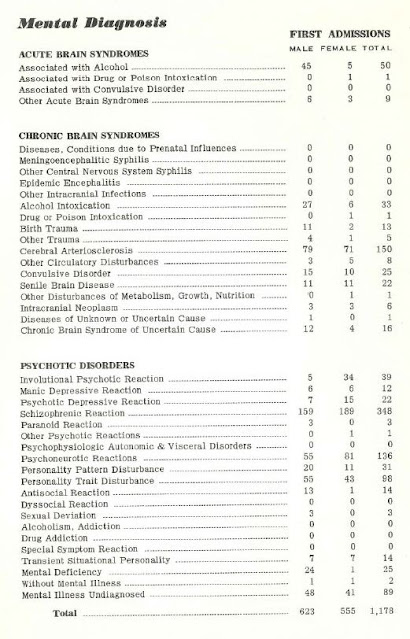

I have been rather naughty in theorising that Smith/Number 6 has an antisocial personality disorder specifically because it was a condition that in the sixties was even worse diagnosed and treated than it is now. The personality disorders were still part and parcel of the hospitals' work then, and here we have the diagnoses for people on their first admission at Arizona State Hospital in 1963 (from their annual report) which to me is fascinating reading. We have the characteristic backbone of diagnoses of schizophrenia but I'm not sure because I don't understand the terminology used whether a personality disorder would come under personality pattern disturbance or personality trait disturbance, and they have a good number of each. Incidentally I hope the people diagnosed with no mental illness was discharged and wonder how on earth they managed to get 89 admissions with 'mental illness diagnosed'. Heigh ho.

You may argue that in this episode it is explicitly said that Smith/Number 6 is not 'mad'. Well I can reveal that since we're overhearing a conversation behind the scenes the staff are being rude. What they mean is that Number6/Smith is not 'mad' or ill in the sense of having a mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. They're making the classic distinction between mad and bad - and saying that Smith is mentally disordered but not ill in the sense of having an illness like schizophrenia.

Here are the World Health Organisation's diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder (ICD - 10 version):

Personality disorder usually coming to attention because of a gross disparity between behaviour and the prevailing social norms, and characterized by

(a) callous unconcern for the feelings of others

(b) gross and persistent attitude of irresponsibility and disregard for social norms, rules and obligations

(c) incapacity to maintain enduring relationships, though having no difficulty establishing them

(d) very low tolerance to frustration and a low threshold for discharge of aggression, including violence

(e) incapacity to experience guilt and to profit from experience, particularly punishment

(f) marked proneness to blame others, or to offer plausible rationalizations, for the behaviour that has brought the patient into conflict with society

There may also be persistent irritability as an associated feature. (2)

I honestly think that when you turn the relationship between Smith and the Village round the way I did at the start of this post he has all of the features. I would also posit that he has been violent and possibly even killed Seltzman, and has been sent to the Village by the court as being too mentally disordered for prison, but he still isn't talking about what's actually happened. In fact at the time The Prisoner was made, violence was more usually associated with this personality disorder than it is now. As I have said before I would suggest that he has an index offence which is covered in his own mind by his resignation story as a defence mechanism, and the offence is what the Village authorities want to get out of him but they are terrified of him and tend to talk about it in terms of his own defence.

Because it's all the Village's fault, obviously.

And here's what antisocial personality disorder feels like for the person experiencing it (it's not half as dramatic as it can sound and more messes with your own life):

My name is Andy, I am 33 years old. I am diagnosed as having severe antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).

This is the clinical diagnosis which is synonymous with the words psychopath or sociopath.You might have some ideas about what that means, and therefore what sort of person I might be.And you wouldn’t be alone.A quick google of this diagnosis will reveal a character assassinating portrait of a person incapable of empathy and hell bent on destruction of themselves, others or both.While this may happen in some instances it does not happen in all of them, contrary to what the media would have you believe.I know that because my life is not how they say it is, or should be.Here’s what it’s actually like.My childhoodI was born in 1984 to a woman who had no maternal instincts and neglected all of her children. My biological father had schizophrenia, took drugs and later killed himself. This meant that at only a few months old I was taken by social services and placed into a foster home.Then, at just over 2 years old I was adopted. I was brought into a family that have shown me so much love and understanding throughout my life it is truly incredible. A lot of people idolise their parents but mine really are amazing. I have yet to meet two other people who are so loving and compassionate.But then between the ages of 7 and 10 years old I was sexually abused by a friend’s older brother. My parents were unable to stop it at the time, as they didn't know it was happening. I never told anyone until afterwards.It is the belief of the psychiatrists that I was genetically predisposed to an antisocial/psychopathic personality and the combination of a disrupted early 2 years of life and the later sexual abuse ‘triggered’ it."During and after the sexual abuse I became more aggressive and violent. As a child anger seemed to be my only way to express how I felt, although looking back I have no memory of any feelings."To this day if I think of any of the things that happened during those years I see them very clearly but with no emotion attached. This is something which is true of all my memories from this time, not just the abuse.The abuse stopped (because we moved house for my father's work) but my behaviour continued to deteriorate, especially during my teenage years.My teenage yearsI was angry and hostile, my behaviour lead to me being excluded from school and I was violent towards animals.Even though I always had plenty of friends and was popular at school, inside I felt I didn’t fit properly. When I grew up and found out my diagnosis, I knew that was the reason why.At the age of 16 I was seen by a 'top' clinical psychologist. He assessed me and despite me being completely honest with him he gave me ‘a certificate of sanity’, laughed and sent me on my way, I can still remember his face as he said it.But looking back it was clear I was not ok. Two years ago I requested all my medical records and I was able to read what he had written, what my parents had said to him and also what my GP had mentioned.I am still truly astonished that being a psychologist with the reputation he had, he could not see what was clearly sat right in front of him.If he had it is possible that my life would have taken a different course.My double lifeBut it didn’t, so things continued as they were. After finishing my A Levels where I once again underperformed, I started working."I had no clear path in life and wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. Even now all these years later, I still don’t."I have ideas about things and careers but because I’m perpetually bored it’s hard to do something that is satisfying in the long term. People have careers and goals that they can throw themselves into and be passionate about. I am completely unable to do that.Through a job I got as a door supervisor I met people involved in all sorts of criminal activity. By the time I was 21, I was one of them and got my first conviction for robbery. However I hid this from my friends and family and continued life as normal.I now know that this is when I first was first diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder. Remarkably the doctors never told me, although they wrote it down and shared it amongst each other.They prescribed me anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medication which whilst seeming to dull my senses slightly did nothing in addressing the underlying problem. And not once was I ever told what was wrong with me.I lived a double life. On one side I was a self-employed computer technician and on the other I was serious criminal. This continued until I ended up in court again. I was told by my barrister that I would probably go to prison.And I suppose this was the turning point. When I decided to make a permanent change for my sake and the sake of my family whom I love very much.My life nowMy partner was pregnant you see, and I would miss the birth of my daughter and likely the first few years of her life if I went to prison. Not to mention the thought of being trapped in a cell was terrifying.It was at this point whilst trying to better myself that I was finally told my diagnosis was severe antisocial personality disorder. I had gone to seek help because I thought I potentially had ADHD, a fairly logical conclusion because of my impulsive thrill seeking behaviour and low boredom threshold."After being told my diagnosis I was then able to understand how and why I behaved the way I did: my life made a little bit more sense."I was able to begin learning new ways to live that would enable me to be a ‘normal’ family man, a good partner and a responsible father. Up until then I had not known what was wrong with me and so I was unable to deal with the problem.This has not been an easy journey. I have had several jobs since 2011 and I have found out a lot about myself and my personality and what my strengths and weaknesses are.I would be very surprised if anyone who has met since 2011 would think there was anything wrong with me.The only thing unusual about me (if it even is unusual) is the struggle of being permanently bored and restless.My mind and body seem to need so much stimulation it's almost painful. Since 2011 I have channelled this into exercising, mainly weights and strength training, and also into reading and I love puzzles.I often look at people just sat contently watching television and wonder how on earth their minds are so peaceful.As I am now I know I would never go back to a life of crime and I have no desire to do so. Now the struggle is discovering what to do next, something which I think about every day. But I still don't know.The stigmaDuring this time I have also seen a private psychiatrist and we talked about my diagnosis and how can it be that I am ‘psychopathic’ but able to love my family.She informed me that I am capable of love and empathy with certain people that I am close to but outside of this I am completely remorseless.This is something which my family have struggled greatly with since learning of my diagnosis. And to be honest, in some ways I wish I hadn't told them.Once they googled it, they instantly came across sites and forums dedicated to this topic. All of which insist I am incapable of loving anyone but myself, and that any signs I do is only so I can use and manipulate them.But I strongly believe the majority of studies done on ASPD are on dangerous criminal 'psychopaths' who are in prison for serious crimes. While there are a huge number of people, like me now, who are not violent or criminal, and live normal lives.But that frustration I have with my family soon subsides. As I know, without their help and support I wouldn’t be here. I am truly grateful to have been blessed with them. And ironically it’s that love that I feel for them every day, which lets me know what they, and others, think about me is not true. Source

Now you know why Smith/Number 6 is continually irritable and upsets everyone in the Village: it's just he also doesn't accept why himself.

(1) Erving Goffman: Asylums. Garden City: Anchor Books, 1961, p. 53 - 54.

(2) Cited in Jose Luis Carrasco and Dusica Lecic-Tosevski: Specific Types of Personality Disorder, in Michael G Gelder et al (editors): New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (Second Edition). Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009, p. 865.

If you would like to support me and this blog you can buy me a coffee (or a box set) here.