The Prisoner in the Asylum: The Chimes of Big Ben

The introduction and master post to this series of posts about The Prisoner can be found here.

I am absolutely delighted to say that although I didn't think it would, because I thought it was too espionage-based, The Chimes of Big Ben has given up much that is interesting in psychiatric terms. Admittedly it took much interrogation and the use of truth drugs.

It is also one of the episodes which has a number of questionable aspects and inconsistencies, and I'm delighted to announce that when you assume Number 6/Smith is in a hospital, a lot of these can be resolved with a glib ready answer that I will give later.

But how do we know it's a hospital? I'm going to be very simplistic here and say that we know it is because Number 2 says it is when he says that Number 8 is there with nervous tension. The fact that Smith thinks they're trying to get information out of her is his misinterpretation.

First I would like to focus on an apparently insignificant scene which would have had a great relevance to psychiatry as known to the intelligentsia and the dinner party circuit in the sixties. It is the scene where unethical experimentation is being done with the electrified floor. At the time this would have be inexorably reminiscent of Stanley Milgram's obedience experiments where he got subjects to give apparent electric shocks of increasing severity to another subject who was actually in on this and wasn't getting any shocks at all. Milgram reported that in 60% of the experiments the subjects continued to give shocks even after the person receiving the shocks stopped responding and may even have been dead. For decades this was used to teach health professionals that human obedience is a dangerous thing. Significantly from the point of view of The Prisoner, the experiments were done against the background of the trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, and the natural conclusion was that the Shoah could happen anywhere, and there was nothing particular about the Germans that made it happen there. Even more ironically from the point of view of the show even at the time the ethics of the experiments were greatly questioned, mainly because he got the participants to consent but to a memory and learning experiment, not to the experiment that was actually taking place, and his membership of the American Psychiatric Association was put on hold because he did these experiments with no theoretical framework of what would make people just do this. It has since been revealed that he only published a very slanted sample of the experiments he did. To cut a long story short, the research, at least as it was presented at the time, is largely worthless. To add the ultimate irony to this, Milgram actually did have evidence which he didn't publish, which would have given him a clear theoretical basis for his experiments and he could have gone with that - what made the participants give apparent electric shocks to people was if they didn't believe the shocks were actually happening. The participants who saw the experiment was fake gave the shock. So all he proved was that you do terrible things if you don't believe they're actually happening!

Have a look at some terribly flawed psychological research in action:

Of course I have my own unique perspective on this and obviously the problem is attributable to having electrical sockets in the bathrooms in the US. Now there's a theory Milgram could have tested. You're welcome.

Nonetheless this research was widely chattered about in the sixties and I would suggest it is suggested in the electric shocks and its reference to concentration camps is mirrored in The Village and the fact that people will just do what they are told there.

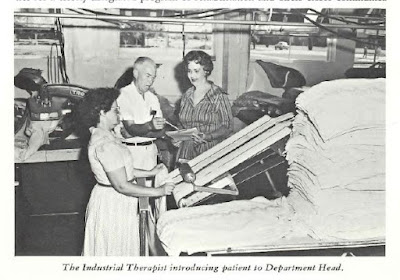

The art competition is a straightforward indication of the the sort of activities which used to go on in the old hospitals and which had some therapeutic or economic significance beyond merely being entertaining. Obviously The Village is a very well-funded, luxury hospital and so has no need of the residents' labour. In many hospitals there was a thing called 'industrial therapy' which was intended to reflect the world of work. Putting rollers for perms together was a common industry, and many of the patients worked on the hospital farm which would help make the hospital self-sufficient.

The main problem with this episode, which I think is adequately answered by the psychiatric hospital explanation, is that it makes literally no sense at all. Is anyone seriously suggesting that Smith will try to abscond from The Village, where he has already referred during this episode to the surveillance and knows that escape attempts will fail, with Number 8 who he has already been very wary of, in a home made boat with a sail depicting Number 2? Seriously? This just wouldn't have happened because it is too irrational for words and doesn't represent Smith's known attitude towards The Village.

Instead I would suggest that the whole escape sequence after the art competitions can be interpreted as either a dream or as an expression of Smith's illness as expressed in therapy. That's why it makes no sense.

In fact when interpreted this way all the other odd things about the episode can be either explained or excused by Smith's mental state or else that he is dreaming. They include (I am very indebted to this page for help with this list): Smith is twice seen in two places at once; the vegetable box of his fridge is completely filled with enough shelled peas to last most people a year; it makes no sense that he won't give Number 8 his name, because she will either already know it if a plant or he can be contrary by giving it; there are two older men building an age-inappropriate sand castle; Smith uncharacteristically assumes that the busts in the wood can't hear; there are a number of geographical inconsistencies in the escape attempt; the way all the art exhibits look like Number 2 can only refer to a dream or a mentally unwell state; there is no apparent way they have communicated their arrival to the man waiting for them in 'Poland'; Fotheringay has a decoration from cottage Number 6 in his office and finally, in the alternate version of this episode Fotheringay bizarrely says that he and Smith were at school together. This is ludicrous because Richard Wattis and McGoohan were born sixteen years apart so this statement has no credibility at all. Of course some of these would have originated as simple continuity errors (or rather disasters) but I think some of them are so bizarre and indicative of a dream state or psychosis that they are better explained in that way. Considering McGoohan's reputation as a control freak this number of strange things is genuinely surprising unless deliberate.

Finally although I have decided to resist the temptation to interpret Smith's dream, the thing which pushes this into dream or paranoid delusion territory for me is the locus of the destination at Big Ben. Just to make this abundantly sledgehammer clear: Big Ben is not just a bell in a clock, because the clock is situated in the Palace of Westminster and is therefore representative of the State, the government, the Lords and even the Church of England. The chimes of Big Ben represent Britain, and wherever we've gone to pillage and ruin other countries, our invaders have dreamt of that as the personification of our nation. That's why we broadcast them on the radio. Those chimes ARE Britain. Nadia and Smith are not merely going to some government office: by situating the office so close to the Palace of Westminster, the episode is placing Smith's paranoia right at the seat of government. In fact I think his mental state places him right at the seat of government although of course this is unreal.

I forgot that next weekend is the jubilee weekend for the queen's platinum jubilee, so call this video of the clock striking the blog's memorial of the occasion. I love a nice clock. My dad collected and restored grandfather clocks and at one point we had four of them in a row on the landing. Because they were never quite right one could be guaranteed to strike thirteen most days! The restoration has made the words, Lord save our Queen Victoria the First strikingly clear, don't you think? But she only reigned just under 63 years.

If you would like to support me and this blog you can buy me a coffee (or a box set) here.